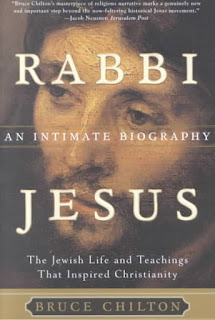

Rabbi Jesus (english)

Hier geht es zur deutschen Version

Bruce Chilton's book "Rabbi

Jesus" portrays a fully human destiny what occurred two thousand years ago

in ancient Galilee. Chilton precisely depicts the political, social and

cultural (Jewish) conditions under which Jesus grew up. Based on

several scholarly options Chilton constructs startling and still highly

plausible hypotheses about Jesus' psychological and spiritual development.

Chilton tries "to understand Jesus on his own terms rather

than in the categories of conventional scholarship and theology". Thus

Chilton's alternative picture of Jesus challenges and sometimes contradicts

traditional concepts.

Chilton's

Jesus suffers from the same doubts and concerns and struggles with similar

problems that beset other people. "Jesus’ force resides in his vulnerability (…)

throughout his life. He entices each of us to meet him in that dangerous place

where an awareness of our own weakness and fragility shatters the self and

blossoms into an image of God within us." Chilton brings the

reader in touch with the "inner man" and occasionally goes beyond the

scriptural warrants. He deals with logical surmise, but this is always clearly

stated in the book, and Chilton never leaves doubt that the story could also have been

reconstructed in different ways.

A fully human destiny that changed the world

Jesus' colorful biography ends up in

a tragic but triumphal personal failure. For "Jesus never accomplished the

Galilean reformation of the Temple (at Jerusalem) that he so passionately

desired and dramatically attempted." The Temple he revered was demolished

as his own body was. "He did not make a lasting mark within Judaism. Dead

at thirty, he had not yet framed his mishnah, the formally crafted public

teaching that a rabbi typically transmitted to his students by around the age

of forty."

A great goal has yet to be achieved

But the final disaster at the Roman

cross eventually proved to be the outset of the great success story of

Christianity, something what Jesus probably never had in mind. For Chilton far

too much theology has been "preoccupied with exalting Jesus as the only

human being sitting on the right hand of God". Many theologians have

"denied heaven to others" because they ignored the "vital truth"

of "how Jesus taught his vision and how he crafted a discipline for its

realization".

Chilton sees a great goal that

"has yet to be achieved: to share Jesus’ vision with all humanity. The

rabbi from Nazareth never claimed he was unique. His Abba was the Abba of all. Jesus

never articulated a doctrinal norm or a confessional requirement, but the

events of his life, his public teaching, his kabbalah[1] gave rise to distinctive,

emotionally resonant rituals such as baptism, prayer, anointing the sick, and

the Eucharist. His transformative visions persisted among those who hope that

the pure of heart will indeed see God and become intimate with him. He remained

a measure of how much we dare to see and feel the divine in our lives."

My own perspective

I have read Chilton's book from my

perspective as a medical doctor and psychotherapist. My professional concern is

to relieve human suffering, fear and despair, including my own. Positively

speaking, I want to support people to feel better, empowered, strengthened in

their confidence in life and in themselves. I do so on the basis of my

psychodynamic background. That means, I try to understand a person's

unconscious needs and motivations, inhibitions and fears, and all the other

forbidden and therefore repressed affects involved. I also try to find out the

person's unconscious believes, concepts, and goals.

Moreover, the question is vital for

me, under which conditions religion is helpful for mental health, for wellbeing

in general, and particularly for coping with life crises and approaching death.

A personal experience became decisive for my own professional and spiritual

development. In a period what felt to me like the most difficult in my life I

was in a state of desperation. All my medical and psychological expertise

seemed to be useless. Even my doctor colleagues were unable to help me.

Eventually I found relief and finally something like healing through the care

of a friend and pastor of a German Free Church. Thinking back I am still

impressed by the extent of attention, compassion, affection, and assistance I

received from him and other members of his church.

When I felt better I tried to

understand the forces and the concepts what made my friend and pastor that

efficient. He himself saw all his power grounded in Jesus Christ. The way he

spoke about Jesus was so much animated that it appeared to me as if my friend

just had come back from lunch with Jesus. My pastor friend emphasized that he

was continuously in a deep and close relationship with Christ. I loved the

emotional quality, "the energy", he conveyed and desired to grasp it

more profoundly.

The result of my research was

disillusion. Behind all that fascinating enthusiasm and loving care I

discovered a tough Christian fundamentalism saying: If you do not worship Jesus

as God you will be lost and condemned to go to hell. Other religions are

idolatry, Islam even devil's work. Judaism has to be converted to the only true

belief in Christ. Unwavering faith, extensive prayer, and invoking the Holy

Spirit are considered the best and sometimes only remedies and solutions for

nearly everything.

In light of my own experience of

both dedicated support and disturbing dogmatism in a Free Church I was

delighted to read Chilton's reconstruction of Jesus' life, depicted as an

extraordinary, but still all human personality and career. Chilton provides

rational explanations for the healings and miracles Jesus performed, also for

his Transfiguration and Resurrection. Still Chilton does not deny a parallel

universe, a reality beyond what we can perceive and comprehend.

Emergence of inclusion

Jesus never intended to create a new

religion. The old Galilean loyalty to the Torah was in Jesus' bones. All he

taught and practiced derived completely from his Jewish background, especially

from the Galilean tradition of verbally transmitted religious knowledge that

Jesus had deeply internalized. However, in Chilton's book it becomes obvious,

that over time inside of Jesus and within his movement something fundamentally

new emerged, what we call "inclusion" today. Unequivocally practicing

it by inviting the most despised members of the Jewish society to table

fellowship, was unprecedented in the Judaism of that time. Jesus himself had

terribly suffered from social ostracism. His own painful experiences helped him

to gradually overcome his ethnic and religious prejudices which derived from

his rural Galilean upbringing. He opened up his heart and his mind not only for

his fellow Jews but also for alien people and social outcasts. And he

encouraged his disciples to follow his example.

Chilton demonstrates strong evidence

that Jesus was a mamzer, i.e. a child of suspect paternity. His parents, Joseph

and the thirteen years old Mary, had slept together before their marriage was

publicly recognized. Due to his illicit conception Jesus had an extremely

difficult status in the small village of Nazareth what made Jesus particularly compassionate

with all sorts of social outcasts. Being highly sensitive for what it meant to

be excluded from social life he eventually broke with custom and dared –

against all inner and outer obstacles – something extraordinary: He celebrated

communal meals with people deemed as impure.

Chilton verbatim: "Jesus was

speaking from personal experience; he had himself known poverty, hunger, the

bereavement of a protective father, and ostracism. He knew when you are

exploited and alone, you are in the best position to identify the sustaining

force of God’s compassion. The poor, hungry, and shunned were Jesus’ people.

Many were virtual untouchables, viewed by observant Jews (some of them

Pharisees) as unclean. Yet Jesus ate and drank with them. We often see him

attacked for consorting with 'publicans [agents who collected customs and

taxes] and prostitutes' and claiming they enjoyed God’s preference."

For Jesus all Israelites and also

their land were already pure. He opposed the prevailing Pharisaic assumption

that purity still had to be achieved. He taught: "There is nothing outside

a person, entering in, that can defile one, but what comes out from a person

defiles the person". Jesus used the innate cleanness of Galilee and its

people to invoke the presence of God at their meals. Drinking and eating

together was celebrating and enjoying God's Kingdom in their midst from which

compassion emanated and what made them forgiven and acceptable to God.

According to Chilton the meaning of

the meals shifted in the last phase of Jesus' ministry. After years of working

with Aramaic sources and anthropological studies of sacrifice Chilton opposes

to the traditional understanding of the Eucharist and concludes: "The

meals were Jesus’ last, desperate gesture, that his own meals were better

sacrifices than those in the corrupt Temple. When Jesus spoke of his 'blood'

and 'flesh', he did not refer to himself personally at all. He meant his meal

really had become a sacrifice. When Israelites shared wine and bread in

celebration of their own purity and the presence of the Kingdom, God delighted

in that more than in the blood and flesh on the altar in the Temple."

Chilton insists that Jesus cannot have meant: “Here are my personal body and

blood”, that interpretation makes sense only if Jesus distinguished himself

from Judaism. The only meaning of his words was that wine and bread replaced

sacrifice in the Temple.

Why was Jesus crucified?

Members of the Sanhedrin, the supreme

council and court of the Jewish people, like many other observant Jews in Jerusalem were offended

by that scandalous new element in Jesus’ practice. He had made his meals into

an altar that rivaled the Temple’s altar. The Temple cult at Jerusalem was

economically highly important for both the Romans and the Jewish priest cast.

They could not allow Jesus to debase it. Furthermore Jesus had urged resistance

against paying the customary tax for the Temple. The Temple was not to be

supported with currency, but by the offerings of one’s own hands, according to

a Zecharian prophecy Jesus was determined to fulfill.

The book of Zechariah (chapter 14)

predicts that God’s Kingdom will be manifested over the entire earth when the

offerings at the Temple are presented both by Israelites and non-Jews. It

further predicts that these worshippers will offer their sacrifices themselves,

in the Galilean manner, without the intervention of middlemen. The book also promises

that “there shall never again be a trader in the sanctuary of the Lord of hosts

at that time” (Zechariah 14:21). Sacrifice in the Temple would be an universal

feast with God, open to all peoples who accepted the truth. Jesus believed the

apocalypse was coming soon and that the world as he knew it would end.

As surreal as the Zecharian

apocalypse may seem to many of us, it did change history, although not in the

ways Jesus anticipated. Chilton clarifies that Jesus had become a serious

menace for the ruling class. Already his exorcisms and his healing powers had invited comparison with

the greatest of Israel’s prophets: Elijah, who had brought the son of a widow

back to life. The memory of Elijah during the ninth century B.C.E. had always

been linked to his resistance to King Ahab and Ahab’s accommodation to foreign

deities. Herod Antipas was just such a collaborator, who had already been

challenged by John the Baptist and had reacted with deadly force. Jesus

ministry had come to Herod’s attention, and he knew of Jesus’ connection to

John the Baptist.

Jesus believed to speak and act with

prophetic authority. Prophets in the mold of Elijah confronted the rulers of

their time with the threat of divine judgment, reinforced by means of signs.

Elijah’s authority had been confirmed by prophetic feats that were often

destructive: he brought about drought and deluge (1 Kings 17:1–7; 18:41–46),

called down fire from heaven to consume a sacrifice (1 Kings 18:25–38), and

killed the prophets of the god Baal (1 Kings 18:39–40). Elijah's signs

encouraged revolution in the name of God. By the first century, many Jews

believed that God would again send Elijah.

The first century saw several

examples of men who took Elijah as their model. They promised their followers a

sign, then a revolution. On each of these occasions, when the would-be prophet

announced the promised sign and then called for armed rebellion against Rome,

the Empire reacted swiftly and the aspiring prophet was killed before he could

enact his promised sign. No publicly acclaimed prophet was only a religious

figure but a potential military threat. Also Jesus and his followers appeared

as a potential army, a band of revolutionary rabble rousers. Galileans compared

Jesus to Elijah, and his prophetic fame branded Antipas a greater threat than

John the Baptist.

Among Jesus' followers were many

zealous Galileans who hoped that through Jesus they would be powerful enough to

enter the Temple and free the land of Herod Antipas and the Romans. Chilton

holds that it was not only visionary fervor that propelled Jesus toward

Jerusalem, knowing that this step was dangerous. There was a realistic side. By

enacting the Zecharian prophecy he hoped that everything might change without a

military revolt. He would lead the ragamuffin band of Galileans to the Temple to

lay their Galilean sacrifices on the altar. God would be moved to reenter

Israel’s history, and the Kingdom would come. Without knowing it, he was coming

to Jerusalem at exactly the time that the Temple itself had been turned into a

marketplace.

For

Caiaphas, Israel's high priest, had recently ordered the vendors of sacrificial

animals in Jerusalem to move from the Mount of Olives to the Temple itself. This was to protect the

animals from being injured on their way and from failing to meet the exacting

criteria to be accepted for sacrifice (besides, it was hard to know which

animal was yours in the confusion of herds). But from the point of view of the

Pharisees and most Jews, trade on the southern side of the Great Court was anathema.

The Pharisees insisted that the act of sacrifice should be a noncommercial

encounter between the people of Israel and God.

When Jesus entered the Temple in the

early autumn of 31 C.E. and saw the vendors' busy transacting business in the

Great Court he felt a catastrophic contradiction of Zechariah’s prophecy. How

could he and his followers enact the final, apocalyptic sacrifice predicted by

Zechariah in a Temple that had been defiled? After three days he returned with

his supporters, 150 to 200 men. Jesus shouted: “Is it not written that: my

house shall be called a house of prayer for all the Gentiles? But you have made

it a cave of thugs.” His followers overturned the vendors’ tables, released the

birds, untethered animals and drove them out the ceremonial gate on the west

side of the Temple. The vendors were pushed and dragged out of the Temple by

Jesus’ followers. Others were beaten, punched, and kicked. There was at least

one murder of a vendor by Barabbas, one of the many violent militants who had

attached themselves to Jesus.

The Cleansing of the Temple had

Jesus made an hero. Large numbers of Jews had opposed Caiaphas' moving the

vendors into the Temple and showed sympathy for Jesus’ occupation. Especially Galileans

were appealed: Jesus was speaking the language of their revolution, centered on

the act of sacrifice. Months later, in the year 32 C.E., Jesus returned again

to Jerusalem simultaneously with thousands of devout Jews who streamed into the

city for the festival of Passover. Many pilgrims had heard of Jesus and fell in

with his company. The processional march became a delirious event. The crowds shouted

their expectation of the Kingdom of God, which they knew was Jesus’ focal

concern, and they sang out that expectation in Davidic, messianic terms: "Blessed

is the coming kingdom of our father David, Hoshannah in highest heights!"

Jesus had consciously played up the

Davidic lineage that he claimed through his father, Joseph. As David’s son, a

wise, healing master of demons in the lineage of Solomon, Jesus now led the growing

numbers of his followers, including his brother James, to Mount Zion. Although Jesus’

focus was on sacrifice in the Temple, rather than military revolt, some of his

followers still clung to the hope that his intention included direct action

against Rome and its minions. For Caiaphas a new Galilean insurrection in the

Temple seemed imminent. His police force was not strong enough to control the

violent reaction he might face if he tried to arrest Jesus. He turned to Pilate

and convinced him that Jesus was not just an harmless lunatic. He denounced

Jesus as the source of an illegal movement of violent opposition centered in

the Temple. Jesus had to be arrested with Roman support.

The death sentence

Jesus

had repeatedly provoked conflicts with Pharisees and priests. The Pharisees had

blamed him for his table fellowship with impure people. Jesus was repeatedly

attacked not to keep the Shabbath and not to respect the laws of dietary and

ritual practice of purity during his holy feasts. He had even claimed a spiritual

authority greater than the Pharisee's and priesthood's. But Jesus had not

actually blasphemed the Temple or the Torah. He had not said anything against

what Judaism held sacred. The charges against Jesus did not

necessarily compel the death penalty. Jesus had supporters among the Pharisees and even

within the Sanhedrin. Nicodemus, a member of the Sanhedrin, could not find anything

specific with which to charge Jesus. It was not easy for Caiaphas to justify

Jesus' conviction.

When Jesus had cited Jeremiah 7:11, equating

Caiaphas’ arrangement in the Temple with “a cave of thugs”, he implicitly had invoked

Jeremiah’s prophecy of the Temple’s destruction, what could easily be distorted

into the claim that Jesus wanted to see the Temple destroyed. Jesus’ message had

not been the Temple's demolition. But Caiaphas and his supporters encouraged

precisely that distortion, to whip up opposition to Jesus. Still such

prophecies were no capital crime. Therefore Caiaphas focused on a more

fundamental question. He asked: "Are you teaching that your feasts replace

Temple sacrifice because you are God’s own son?" Jesus answered: "I

am, and you will see the son of man sitting at the right of the power and

coming with the clouds of the heaven!"

Chilton holds: "Silence at this

point might have saved his life, but not even the high priest was equal to

Rabbi Jesus’ obstinacy." This was a curse from Jesus’ own lips, that his

authority delegated to him by God was greater than the authority of the high

priests, mandated by the Torah. According to the theology of first-century

Judaism, if you attacked any divinely sanctioned institution you were

denigrating the God of Israel and exposed yourself to divine retribution,

either directly or through the decisions of Israel’s courts. Even among Jesus'

own followers Judas was not the only disciple who was disaffected by Jesus' direct

challenge of established ritual tradition in Israel and who deserted him.

Development of Jesus' particular mystical spirituality

Over time Jesus developed a

particular mystical kind of spirituality. According to Chilton the mystical

quality of Jesus' spirituality explains both the miracles he performed, and the

experience of the resurrected Jesus, that many of his followers shared after

his death. Chilton considers the ostracism and the forlornness that Jesus faced

as a child as important factors for his spiritual development. Chilton imagines

a small child, standing apart from other children, wishing to play but not

being included, defensively ironic about the gang’s incapacity to agree on a

game. Jesus must have spent much of his time alone. All the insults explain why

Jesus came to see God as his father, his Abba in Aramaic. If Joseph’s

fatherhood was in doubt, God’s fatherhood was not.

Chilton explains that Jews of this

time recognized themselves as God’s children and addressed God as "our

father, our primordial redeemer is your name" (Isaiah 63:16). To call God "father"

signified that the creator of the entire world had entered into a special

relationship with Israel, as a father to his children. And Jesus joined some

rabbis in a further, bolder claim, asserting God’s personal, fatherly care for

his children as individuals. Aramaic stories in the Talmud show that

"father" was a Jewish way of referring to God, and when Jesus was a

rabbi he instructed his students to pray regularly to God as Abba. The divine

relationship became particularly intimate with Jesus.

From the age of ten, when Jesus had

joined his biological father travelling as a journeyman he got in contact with

the variety of folk tales and different unique ways of rendering Scripture in

its Targum (the Aramaic word for “translation”). Targums are paraphrases of the

Hebrew Bible translated in Aramaic. They represent the oral “Torah on the

lips,” what Jesus and the other illiterate Jews (the majority of the Israelites

of his time) used. A Targum was not a mere verbatim translations of the Hebrew

texts. Those who memorized, translated and recited the oral Scripture added

whole paragraphs and paraphrased long sections. Targums were the foundation of

the faith of the ordinary people. According to Chilton they are the key to

understand Jesus’ Judaic orientation and the vocabulary of his teachings.

Later Jesus became a master of the rich

oral traditions of Galilee. He improvised with their themes and created so many

parables and metaphors. The Kingdom of God was the pivotal hope of Galilean

Judaism. Jews believed that God ruled them and that one day his Kingdom would

be the only power on earth and in heaven. The Hebrew Bible claims that God

helps his chosen people conquer their enemies when they keep his covenant, and

lets them fall victim to oppression when they stray from righteousness. Many

Galileans believed that if they lived in accord with God’s commandments and

prohibitions, God would drive the Romans out from Israel and institute a reign

of justice.

The Kingdom of God became the

principal theme of Jesus’ message throughout his adult life. When his father

Joseph died, the Kingdom of God was the only support and the only thing for

which Jesus yearned at the core of his broken heart. Jesus' Jewish tradition saw

God’s immanence everywhere, in the force of a mustard seed and yeast. Later, as

a rabbi, he saw the divine Kingdom in how one person relates to another. Chilton

suggests that even as a child, Jesus had a direct intuition of how his Abba,

moment by moment, was reshaping the world and humanity. Like other great

religious teachers, emotions led Jesus to an insight put into words only later.

Chilton claims that already as an

teenager (during a visit in the Temple of Jerusalem) Jesus abandoned his family

and the daily suffering from disdain in Nazareth. He joined John the Baptist

(Yochanan the Immerser), a famous rabbi known to offer ritual purification in

the Jordan River. For Chilton John is the key to Jesus’ crucial teenage years.

Jesus wanted to learn John's way of living God’s covenant with Israel. John's

disciples were willing to endure hardship and deprivation, passionately seeking

the way that brought access to God. They lived in the wilderness, supporting themselves

by food that grows of itself, washing with cold water day and night. When repeatedly

immersed by John the hurt of Jesus' childhood, being an outcast, was healed. Jesus

gained a place in a respected religious group.

John initiated Jesus into the

esoteric side of his teaching. John's path into the mysteries of the divine

mind was a part of the ancient rabbinic tradition. It focused on the first

chapter of Ezekiel that describes the Chariot, the moving Throne of God, the

source of God’s energy and intelligence, the origin of his power to create and

destroy. By meditating on the Chariot, John and his disciples aspired to become

one with God’s Throne. Already Moses had seen God's Throne during an ecstatic

vision while receiving the Torah. The Throne appears again with Elijah's

transport into heaven. The Chariot became the master symbol of Jewish

mysticism.

The majority of rabbis in the

ancient period, Jesus included, were illiterate. Ezekiel’s words had to be

memorized in all details. The initiate’s meditation had to be on the text’s

meaning, not on the mechanics of recitation. The disciples also had to master

the text’s intonation and cadence. The musical phrasing of the words (like

mantras in Hindu and Buddhist traditions) was deemed essential to clear the way

for divine realization. The words themselves were viewed as sacred, imbued with

divine force. Jesus learned to become Ezekiel’s text, embody its imagery, and

master the many other complex texts within Jewish tradition that embellished,

augmented, and refined Ezekiel’s vision. Like any aspiring rabbinic visionary,

he needed a superb memory and concentrated devotion to pursue his quest.

John was like a guru. His voice, his

attitude, posture and gestures during the meditations, his intense mindfulness

and ecstatic vision were as much the text that Jesus learned as the words from

Ezekiel. Jesus learned the secrets of God’s Spirit, which flowed from the

Chariot through all creation. John promised his disciples that just as he had

immersed them in water, God would immerse them in holy Spirit. Immersion in

Spirit would not only lead to repentance and release from sin but also overcome

the basic prophetic criticism of Israel: the lack of compassion and disregard

one Israelite showed another. John expected that God’s Spirit was ready to be

poured out on Israel anew as it had been at the time of Moses. John and then

Jesus were seen as prophets inspired (literally “breathed into”) by Spirit and

speaking directly on God’s behalf.

Jesus believed that the holy Spirit

was upon him and that he spoke for God. Repetitive, committed practice, diet,

exposure to the elements and repeated immersions intensified his vision of

God's Chariot and made him have a vivid vision of the heavens splitting open

and God's Spirit descending upon him as a dove: "You are my beloved son,

in you I take pleasure." Jesus related his experience of Spirit to his

friends, and John and his disciples embraced it as the beginning of the

fulfillment of God’s promise. Expressing deep affection John called Jesus “the

lamb of God”, because in his innocence he embodied both release from sin and

the arrival of Spirit. Jesus received from his fellow visionaries the first

sign of the special role he would play in Israel’s destiny. Some of John’s

disciples said they themselves had heard the voice that spoke to Jesus. Their

communal vision welded them together.

As Jesus grew older and more

confident, his ability to invoke Spirit and the power of his vision of God’s

Throne made him increasingly successful in gathering pilgrims for immersion.

Jesus started to move into settled areas, where he could immerse more people

than John did. Jesus was convinced that the people he invited to cleanse

themselves by immersion were already clean. That was why he could eat with

them. Eating with people was vivid testimony that one considered them to be

pure. Jesus joined in holy feast with them. He spoke of the Abba of all who was

the source of Israel’s blessing: “Abba, your name will be sanctified, your

Kingdom will come.” Jesus gradually replaced immersion with communal meals as

the ritual symbol of the coming Kingdom of God.

Sporadic and short-lived retreats

allowed Jesus constant meditation on the Chariot in which he found solace. Chilton

claims that Jesus began to use a vision from the book of Daniel, an angel with an

human face standing beside the Throne of God, called in Aramaic “one like a

person”, engaged in a cosmic battle with the angelic representatives of the

great empires that had conquered Israel. The “one like a person” brought Jesus

close to his Abba and became the anchor of his visions. Jesus and his disciples

identified themselves with the “one like a person”, what can also be translated

as “son of man”. In Daniel’s vision, God himself intervenes and elevates "the

one like a person" within the heavenly court.

In the mystical tradition of Judaism

of this time, a vision of the Chariot was also called an entry into Paradise,

the original Garden Eden of Genesis. Jesus entered consuming trances, and saw

faith as a means by which people could share his vision of Eden, and be

transformed by its eternal vitality. His healings effectuated the restoration

of the Paradise that was part and parcel of God’s primordial intent in making

the world. Jesus began to insist that his disciples have the same kind of faith

in him that they had in his Abba. This was an outgrowth of his identification

with the “one like the person.” Jesus had begun to see himself as part of the

heavenly court.

On Mount Hermon Jesus was

transformed before Peter, James, and John into a gleaming white figure,

speaking with Moses and Elijah. Years of communal meditation made what Jesus

saw and experienced vivid to his disciples too. Covered by a shining cloud of

glory, they heared a voice say: “This is my son, the beloved, in whom I take

pleasure: hear him.” When the cloud passed they found Jesus alone as God’s son.

The voice did not make Jesus into the only (and only possible) “Son of God”

like the later doctrine of the Trinity. Rather, the same Spirit that had

animated Moses and Elijah was present in Jesus and could be passed to his

followers, each of whom could also become a “son” (like in Buddhism principally

everybody following Buddha's path can become a Buddha).

According to Chilton the story of

the Transfiguration represents the mature development of Rabbi Jesus’ teaching.

He had led his disciples into the richness of the vision of the Chariot by sharing

his vision with them and transforming them. His teaching shifted away from what

can be discerned of God’s Kingdom on earth to what can be experienced of the

angelic pantheon around God’s Throne. It must have seemed to the apostles at

that moment that all the hardships, struggles, and disappointments were finally

rewarded in the intimacy he gave them with the divine presence.

Jesus’ advanced esoteric teaching

For Chilton the most difficult part

of Jesus’ science of approaching the Throne is expressed in Mark 8:31–33,

Matthew 16:21–23,and Luke 9:21–22: "And he began to teach them that: The

one like the person must suffer a lot and be condemned by the elders and the

high priests and the letterers and be killed and after three days arise." Here

the Aramaic phrase “one like a person” is used to designate ordinary human

beings. Rather than a precise foreknowledge of Jesus' imminent death (a later

distortion of its meaning) this text conveys Jesus' deep sense that all of us must

remain aware of our frail, suffering nature in the midst of the vision of the

Throne and its angels. One faces Abba with a child’s vulnerability.

For Chilton one of the pitfalls of

any spiritual discipline is that the practitioner might exalt his own

importance, claiming to be as infallible and powerful as the divine world he

trains himself to see. Forgetting our mortality betrays God, and we run the

risk of supplanting God’s majesty with our own arrogance. Jesus insisted on conscious

acceptance of suffering. Jesus did not treat pain as a virtue in itself, but

turned the endemically human experience of suffering into a means of

discovering divine power in the midst of our own weakness. Danger and suffering

were to be embraced as signs that God’s Kingdom was making its way into a world

that resisted transformation:

"For whoever wishes to save

one’s own life, will ruin it, but whoever will ruin one’s life for me and the

message will save it. For what’s the profit for a person to gain the whole

world and to forfeit one’s life? Because what should a person give for

redemption of one’s life? For whoever is ashamed of me and my words in this

adulterous and sinful generation, the one like the person will be ashamed of

also, when he comes in the glory of his father with the holy angels" (Mark

8:35–38; Matthew 16:25–27; Luke 9:24–26).

The disciples learned that putting

their lives in jeopardy enabled them to stand before the heavenly Chariot with

the one like the person. Jesus reminded them that the prophets of Israel had

suffered for the sake of their vision and for the reward of the vision of God.

He insisted that his followers learned humility, of what he set them an example

in the way he lived. He taught them to recognize that one is limited, weak, in

need of nurture and forgiveness in the presence of the creator of all things. Jesus’

execution became the vehicle for an unconquerable vision. The “cross” he

expected to carry, and expected each of his followers to carry, symbolized the

potential of suffering to serve as the gateway from this world to the realm of

God.

The vision of the resurrected Jesus

The promise of resurrection was unequivocally

articulated in the book of Daniel, one of the Hebrew Bible’s latest works: “Many

of those who sleep in earth’s dust shall awake." Priestly Zadokites argued

that the Torah did not require belief in resurrection, some Pharisees insisted

that one was raised from the dead in the same body in which one had died.

Against the Zadokites, Jesus found the resurrection hope within the Torah

itself, in its reference to the enduring lives of the patriarchs. Against the

Pharisees, he compared the resurrected patriarchs to angels. He never stated

that the dead are raised physically, in the same bodies they had at death. For

Jesus resurrected humans were like angels in the heavens.

For Jesus the transformation from a

physical to an angelic state was the substance of resurrection and inextricably

rooted in a Semitic understanding of human life and personality. The Hebrew word

"nephesh", meaning both life and breath, coordinated body and

breathing within a single, living whole. Nephesh was linked categorically to

the view that God was Spirit, the almighty force of wind breathing life into

all creation. For Jesus human beings could shape their innermost breath, the

pulse of their being as well as their cognitive awareness of the Chariot, to

correspond to the overpowering creativity of divine Spirit. Jesus focuses us on

the essence of our humanity, and allows us into his parallel universe, imbued

with the justice and glory of God. The resurrection is both the most elemental

and the most difficult to grasp of all Gospel teachings. And yet the confidence

that God raises life from death, is still sustaining Christianity.

Chilton suggests a rational

explanation for the disciples' experience of the resurrection of Jesus: Like

Buddha, Jesus was a superb teacher, capable of imparting the inner energy as

well as the outer form of the religious wisdom he had discovered. The disciples’

mystical practice of the Chariot only intensified after Jesus’ death, and to

their own astonishment and the incredulity of many of their contemporaries,

they saw him alive again. The fear and pressure due to Jesus’ crucifixion

intensified his followers’ experience of his angelic persona and their vision

of the spirit world where they, like he, increasingly dwelled. The resurrected

Jesus appeared to them in vision, alive in the glory of the Throne but

profoundly changed. At times, they didn’t even recognize him.

According to Mark (16:1–8) Miriam

Magdalene, Miriam of Yaaqov and Shalome, were the first to have this visionary

experience. Mark speaks of the women's “trembling and frenzy”. Fear and ecstasy

were typical emotions related to the vision of the divine. The angelic young

man the women encountered in the empty tomb signaled that they had entered the

trance world of the Chariot. When he said in the majestic rhetoric of Luke,

“Why do you seek the living among the dead?”, the event we call the resurrection

was born. When Jesus' followers met together, meditated, and prayed, their

journey into the world of the Chariot brought them face to face with Rabbi

Jesus. Chilton suggests that their collective visionary trances engendered a

form of religious hysteria.

When Jesus' disciples returned to

Jerusalem for the great feast of the Pentecost, the wheat harvest, which

occurred seven weeks after Jesus' death at Passover, they gathered privately in

festal meals. They had many experiences of the resurrected Lord what made them

feel vindicated and reenergized. In their understanding, the risen Jesus poured

out on them the same Spirit he had been immersed in since his time with John. The

New Testament records that five hundred other followers in Galilee also saw the

rabbi raised from the dead. Jesus appeared in distant places nearly

simultaneously and walked through doors. He insisted that Miriam of Magdala kept

her hands off him, but invited Thomas to finger his wounds? To understand these

confusing accounts Chilton suggests to see the resurrection as an angelic,

nonmaterial event.

In Paul’s first letter to the

Corinthians, written around 56 C.E., he listed twelve delegates, the five

hundred “brethren” of Jesus, James, Peter, other apostles, and himself, as having

experiences of the risen Jesus. Paul’s own resurrection vision occurred in 32

when he was still named Saul. On a mission from Caiaphas to denounce Jesus’

followers in Damascus he was suddenly surrounded by light. A heavenly echo

identified itself as Jesus of Nazareth. For Chilton this was in no sense a

physical encounter with Jesus. The appearance is depicted very similar to what Jesus'

disciples experienced, complete with prophetic commissioning and the symbolism

of the holy Spirit in the surrounding light.

Saul turned around. After a retreat

into solitude for three years he went back to Jerusalem. He spoke about his

vision only to Peter and James. Chilton holds that Paul understood that his

experience was more visionary than physical, as he carefully says in a passage

of straightforward Greek that has been perennially mistranslated as "God took

pleasure to reveal his son to me.” According to Chilton the correct

translations is “God took pleasure to uncover his son in me” (Galatians

1:16). By distorting the meaning of a single preposition, traditional

Christianity has falsified its premier apostle’s own visionary experience of

what he explicitly (1 Corinthians 15:8) understood to be the resurrected Jesus.

The meaning of what we know about Jesus for our own life and death

According to Chilton's experiences

with terminally ill patients, a little Golgotha awaits us all at the close of

our lives in one way or another. "Fear sometimes makes us wish for a

quiet, sudden and even violent end, rather than confront that inexorable and

unyielding moment. But trying to evade the instant when we truly and completely

lose ourselves only compounds pain with delusion." Standing by the graves

of the people Chilton burries, he is aware that a person has passed beyond our

reach. "Here we know that we all, too, are broken. But Spirit does not

die. (…) The sacrifice of our own lives frees Spirit to fly across the heavens.

There is no one way to die, as there is not a unique wisdom of what dying

means, or a single cross we all have to bear." For Chilton Jesus' "discovery

of who we are in our pain, offers the vision that death’s change is not simply

degradation and despair. It is not the end of us, but the end of who we think

we are. To lose one’s life is to save it. Death is our hardest lesson, but it

is also the gateway into the true, divine source of human identity."

I would like to add some aspects:

Jesus life, as Chilton depicts it, is a fascinating story of human struggling,

development, triumph, error, and failure. Jesus was able to transform his

suffering into compassion and visions. He consequently lived his visions. His

devotedness was complete. He gave thousands of underdogs comfort, hope, self

confidence, and orientation. He resisted the temptation to head a violent upheaval.

Instead he trained his followers to experience a parallel world of divine

peace, justice, and glory. He taught them to trust in it and to transform their

intrinsic fervor for God into care for their neighbors and even into love for

the enemies. He acted as a trustworthy model for what he taught. He

successfully opposed the rigid positions and practices of the powerful and

established new spiritual concepts and rituals that better suited the needs of

the indigents and social outcasts. He left such a strong impression on his

followers that after his death his movement rather than vanishing lived up to

its full potential.

What made Jesus that effective and influential?

How

come an illiterate construction worker from a petty province of the Roman

empire crucially changed history? Was it his divine nature,

was he part of a divine plan as it is taught in churches? Like other great

religious personages, Jesus must have had a particular sensitivity and

receptivity for the reality beyond what we can perceive with our ordinary

senses and what we can grasp with our usual reasoning. He must have had a

particular visionary capacity. He did not only repeat and elaborate the

patterns of his culture, like the Pharisees did, but he generated – always

based on his Judaic background – novel, advanced and realistic ideas and

practices. He was a great reformer of Judaism, maybe the most important. It is

not seriously conceivable that Jesus intended to create a new religion apart

from Judaism.

Chilton's book suggests that the

evolution of early Christianity was not the outcome of the ministry of a single

unique person, but an interactive and reciprocal group effect, to which many

contributed and for which the time was ripe. When John the Baptist had been

executed his disciples had scattered. Some had joined Jesus. Surprisingly

Jesus' death and failure at the cross turned out to be crucial for the unswerving

and unstoppable process of future development of his movement. Obviously Jesus

had created an extraordinary quality of attachment and community with a part of

his followers, and also among themselves. He had bestowed on them orientation, trust

in God and in themselves, and an enormous extent of visionary enthusiasm.

Through him they had found a new assignment and meaning for their life. Already

before he died he had encouraged them to speak and act in his name.

Psychodynamic aspects of the experience of resurrected Jesus

From my psychodynamic background I

would like to suggest to view the apostles' experience of the resurrected Jesus

and of the descent of the Holy Spirit as a manifestations of a particular grief

process. Intensively trained to change their state of consciousness into a

meditative trance and to experience common visions of the divine some hundred

of Jesus' followers were able to transform their fierce longing for their

master into a collective experience of perceiving him alive.

According

to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross there are five stages of grief: denial, anger,

bargaining, depression and acceptance. In the first stage, the loss of the

beloved person is denied, the mourner thinks: "This isn't happening."

In psychodynamic terms denial can be understood as a temporarily useful defense

mechanism preventing the mourner's self organization from collapsing due to the

unexpected bereavement of an so called self object (a person that provides

emotional security and stability). The vision of the resurrected Jesus can be

considered as an expression of the apostles' transient mental state of denial.

But

the vision of the resurrected Jesus is more than just a defense mechanism. The

emotional relationship and the bonding between the mourner and the deceased

person goes on. Important aspects of the beloved person are internalized and

remain alive as a so called internal object. From the psychodynamic perspective

Jesus continued to

live within his followers as a good, stable and nourishing inner object. In a

way the apostles' experience of the resurrected Jesus represented a realistic

part of their inner truth. After forty days of collective mourning Jesus did

not appear to his followers any longer, what is called Ascension of Jesus in

the New Testament. As a rational explanation I suggest that the grief process

of Jesus' followers – facilitated by sharing the pain and sadness – had reached

a stage in which there was no further psychological need for visioning Jesus

alive and denying his death.

Psychodynamic aspects of the experience of Pentecost

Jesus had spent his last years

covert in the wilderness to evade the persecution of Herodes Antipas, the ruler

of Galilee, who had already ordered the execution of his teacher John the

Baptist. In order to go on spreading his message in Galilee, Jesus had dispatched

his disciples as his delegates. He had encouraged them to proclaim God’s Kingdom

in Galilee and to heal people on his behalf. Hence, after his death, his

followers had a lot of practice and were well prepared to continue their

master's ministry. Pentecost, more than fifty days after Jesus' crucifixion,

indicates the moment when the desperation and paralyzation of his disciples had

completely turned into new confidence and determinedness. The New Testament

depicts the recovery of the disciples' power and courage as the descent of the

Holy Spirit.

It is a natural psychological phenomenon

that, after the death of a parent or an important teacher who are role models,

the successors adopt the parent's or teacher's qualities, habits, values,

opinions, goals, visions, and even their mental power. There is a conscious or

unconscious identification with the deceased. When the evangelist John (15,4)

lets Jesus say: "Abide in me,

and I in you", it reflects the simple psychological truth, that after the

death of a beloved parent or teacher the internal attachment of his successors

persists and can even deepen, especially if over time the deceased is strongly

idealized. All religious doctrines seem to have in common that their

originators and were idealized and their objectives deformed by later

generations. It is tempting to project one's own ideas and needs onto an

idealized person who cannot defend herself any more.

How to facilitate relationship with Jesus for people of today?

Many people need a simple

concept of what is right and what is wrong. For them religious or political simplification,

fundamentalism, and intolerance towards other ethnic groups, religions and

wisdom teachings provide a feeling of stability and consistency. Those people

will not be open for Chilton's ideas. But there is a growing number of people

who are not longer reached by the established concepts and by the wording of

the churches. The traditional Christian glorification of Jesus as the only begotten

son of an all-knowing and almighty God, the teachings of virgin birth, original

sin, Holy Trinity, and much more dogmata insult the enlightened mind and do not

correspond to the everyday experience of the majority of modern people.

I am one of them. For me it

is much easier to become friend with a fully human, non-transfigured,

vulnerable Jesus who struggled, vacillated, erred, failed and missed his messianic goal of saving

Israel and establishing God's kingdom. Precisely through his glorious failure

at the cross Jesus caused the very miracle of his ministry: his frightened and

demoralized followers did not scatter and resign although the crucifixion had unequivocally

proved that Jesus was not the messiah the way most ancient Jews expected him.

There was something much more sustainable than political and military power. A

new quality of bonding, solidarity, and mutual care had emerged within the core

group of Jesus' followers. Jesus' movement provided a completely novel answer

to the feeling of collective impotence and despair of the Jewish people in the

first century C.E. and to their deathful hatred against the Roman occupiers.

What can we learn from Jesus and his followers for the challenges of today?

Today

we face an alarming rise of religious and ethnic intolerance, increasing

enmity, war and terror. Unfettered capitalism destroys the environment and the

livelihoods of millions of people. Important public, political and economical

institutions like banks, insurances, and other big business concerns, even the

press and the political system do not seem trustworthy any more to many people.

There is also a growing social isolation and loneliness of millions of

individuals. There is a loss of trust, solidarity and mutual care even in

private relations. The material abundance that capitalism engendered taught us

that the full satisfaction of our material needs does not automatically create

happiness. In contrary many people in the wealthy western countries suffer from

overweight, addiction, prosperity diseases, pressure to perform, burn out,

depression, anxiety and psychosomatic disorders.

The

recovery of trust, solidarity and mutual care seem to me one of the most

important challenges of our time. How could we, how could our world cure

without solidarity, care for and trust in each other and without trust in a

truth beyond of what we can perceive and intellectually comprehend? Trust in

the divine along with solidarity and community with the indigent and the ostracized

were crucial points in Jesus' message and practice. After Jesus' death his

followers did not seek – like the zealots – salvation in futile and suicidal

rebellion against Rome, but strived for inner liberation by the means of

meditation, love and reconciliation. Are those principles applicable to the

problems of today? I think yes.

Christ

In

the Christian tradition of faith Jesus is called "Christ". The Greek

word "Christós" means "the anointed", in Hebrew "Meschiach".

Chilton explains that the

term “Messiah” could be defined in different ways in ancient Judaism. Messiah

could refer to one chosen of God from the house of David to rule as king and to

achieve the expected removal of foreign dominion by war. Messiah could also

mean anointed to offer sacrifice, or anointed to prophesy. The Old

Testament's Book of (the second) Isaiah speaks about a servant of God assigned to

call Israel to its vocation as the people of God and to lead the other nations, but

also to endure horrible suffering:

"He was despised,

and forsaken of men, a man of pains, and acquainted with disease, and as one

from whom men hide their face: he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely

our diseases he did bear, and our pains he carried; whereas we did esteem him

stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted. But he was wounded because of our

transgressions, he was crushed because of our iniquities: the chastisement of

our welfare was upon him, and with his stripes we were healed. All we like

sheep did go astray, we turned everyone to his own way; and the Lord hath made

to light on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed, though he humbled

himself and opened not his mouth; as a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and

as a sheep that before her shearers is dumb; yea, he opened not his mouth. (…) He

had done no violence, neither was any deceit in his mouth. Yet it pleased the

Lord to crush him by disease; to see if his soul would offer itself in restitution,

that he might see his seed, prolong his days, and that the purpose of the Lord

might prosper by his hand: Of the travail of his soul he shall see to the full,

even My servant, who by his knowledge did justify the Righteous One to the

many, and their iniquities he did bear. Therefore will I divide him a portion

among the great, and he shall divide the spoil with the mighty; because he

bared his soul unto death, and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore

the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors." (Isaiah, Chapter 53)

Many

Christians believe that this text heralds the messianic role and passion of

Jesus. Chilton does

not share the view that Jesus saw his role in intentional suffering and in

sacrificing himself. Jesus' own idea of his messianic role was

rather to be chosen of

God and empowered by the holy Spirit for his particular prophesy. There is no

evidence that Jesus considered himself as a divine figure, as the only son of

God or as the lamb of God designated to die for the salvation and redemption of

Israel. Such an exalted meaning of the Messiah

appeared only later.

There is broad consensus among

scholars that the Gospels cannot be considered as literal history. After

280 years of scientific quest for the historical Jesus, Albert Schweitzer's

claim remains still valid that a solid and precise historical reconstruction of

Jesus' life is impossible. But are the Gospel just fanciful Hellenistic fairy tales and useless for

historians? Did the evangelists and later Christian authors even

deliberately manipulated and fraudulently altered the original facts? Chilton

would not agree with such a stance although he holds that the authors of the

Gospels extensively reworked, arranged and edited the available accounts of

Jesus and his ministry.

Everybody

who had encountered Jesus had made his or her utterly subjective experience

with him. Therefore the accounts of Jesus rendered by different individuals

varied of course. The stories and the pictures of Jesus, as they are conveyed

in the Gospels and in the later Christian literature, consist of hundreds,

maybe thousands of individual encounters, emotional reactions, intellectual

preoccupations, spontaneous imaginations, intuitions and interacting

narratives. Thus the Gospels might reveal much more about the needs, longings,

projections, cultural backgrounds and states of consciousness of those whose

experiences and accounts are melted together in the New Testament than about

the real person of Jesus.

If

we do not view Jesus as an unique figure, chosen by God to play the dominant

role in a particular divine plan, but if we look on Jesus as just the prominent

opponent of a collective development process evolving a novel kind of

spirituality and religious practice within ancient Judaism, we must not lament

the persistent vagueness of Jesus' historical profile. Instead we can focus on

the obvious outcome of that process, what was in fact the notion of Jesus as a

divine figure. Obviously there was and there still is a strong need to exalt

Jesus and to exalt oneself by participating in Jesus' messianic glory. According to Chilton Jesus

himself rejected the role of a victorious messiah. He resisted the temptation

of being exalted and insisted that his followers learn the same humility. He

taught them to recognize that one is limited, weak, in need of nurture and

forgiveness in the presence of the creator of all things.

I would like to close my provisional

review by posing some questions: What is the particular Christ quality that

Jesus could have had in mind? What kind of Christ quality is appropriate nowadays?

How can that Christ quality contribute to individual and collective healing, to

liberation from fear, hate and despair, to more solidarity and mutual care, to

preventing the world from further war, terror and ecological suicide?

|

| Bruce Chilton: Rabbi Jesus |

Kommentare

Kommentar veröffentlichen